Happiness is becoming one of the most discussed – and most misunderstood – topics in the modern workplace. We talk a lot about engagement, retention, and productivity, but beneath all of these lies a simple truth: people do their best work when they’re happy. And there is an undeniable link between how people are treated at work, and how happy they feel in other areas of their life.

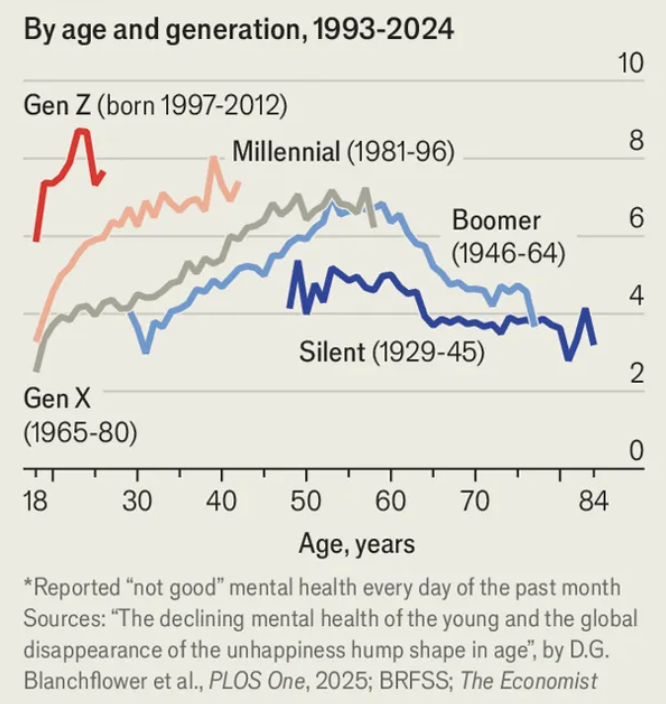

Yet, despite the research, many organisations still treat happiness as a “nice to have.” The World Happiness Report consistently places the US lower than one might expect, and studies like the Global Flourishing Study reveal worrying patterns: young adults today are significantly less happy than previous generations. The workplace is not the sole reason, but it plays a powerful role.

In a recent episode of the #FromXtoZ podcast Danielle Farage and I talked about happiness at work and looked at research from the Global Flourishing Study and World Happiness Report. Here’s my take on our conversation….

The Shifting Landscape of Work and Happiness

For older generations, entering the workforce often meant joining an employer who invested in training, mapped out career paths, and offered stability. There was a sense of reciprocity: employees committed to their employer, and employers committed to developing their people.

Nowadays, many young professionals enter the workplace burdened by student debt, often competing for a smaller number of opportunities (especially in sectors disrupted by technology and, most recently, AI) and often navigating companies who are reluctant to invest until new hires “prove themselves.” Instead of stability, they are encountering uncertainty – and instead of development, they can often face a “sink or swim” mentality.

This lack of investment is more than a skills gap – it contributes directly to unhappiness, anxiety, and disengagement.

The Factors Behind Unhappiness

The Global Flourishing Study found that the unhappiness of young adults stems from a combination of:

- Poor mental and physical health

- Lack of meaning and direction in their careers

- Financial insecurity

- Weakened relationships

When these challenges are layered on top of work environments that lack support, training, and clear pathways, many employees start to feel adrift.

The Chicken-or-Egg Dilemma

Many organisations hesitate to invest in training and development because they fear people will leave. But as the old conundrum goes: “What if we invest in them and they leave? But what if we don’t and they stay?”

Leaders must accept that employee turnover is inevitable. What matters is whether your organisation earns a reputation as a place where people grow, thrive, and feel valued. A workplace known for investing in its people will always attract strong talent. A workplace that withholds investment creates a revolving door of disengagement.

The Role of Leaders: Parenting, Not Policing

Leadership plays a defining role in workplace happiness. The parallels between parenting and leadership are striking. Parents know that over-controlling, fear-driven rules often backfire, while support, guidance, and freedom to explore can build resilience and loyalty.

The same is true in the workplace. Leaders who cling to employees out of fear of losing them can often end up driving them away. Leaders who provide tools, training, and opportunities for growth — even if it means employees may one day leave — build trust and long-term commitment.

Culture and Colleagues Matter Too

Happiness is not just shaped by leaders, but by the culture and people employees interact with daily. A supportive team, a culture of recognition, and a sense of belonging can make the difference between a job that drains people and one that energises them.

Employees spend a large portion of their lives thinking about, or engaging with, their workplace, and if the culture is toxic or indifferent, unhappiness spills into life outside of work. Conversely, when people feel supported, trained, and valued, happiness at work enhances happiness in life.

Who Owns Workplace Happiness?

Some leaders will argue that happiness is ultimately a personal responsibility. They provide the platform and environment…and employees must bring their own positivity. There is some truth to this — no one can outsource their happiness entirely. But leaders cannot ignore their influence.

The reality is that organisations shape many of the factors tied to happiness: financial stability, growth opportunities, meaning in work, community, and recognition. Leaders may not be responsible for every aspect of happiness, but they are undeniably responsible for creating the conditions in which happiness can thrive.

So How Can Leaders Foster Real Happiness at Work?

If you want to foster real happiness at work, then here’s a plan:

- Start Development on Day One Give every new hire a clear onboarding plan and at least one formal training opportunity within their first 90 days. Pair them with a mentor or buddy so they feel supported and can learn informally as well as formally.

- Make Career Conversations Routine Schedule quarterly career check-ins that focus on growth, not performance ratings. Ask questions like: “What skills do you want to build this year?” and “Where do you see yourself in two years, and how can we help you get there?”

- Give Recognition Weekly, Not Annually Make it a habit to acknowledge good work in real time — a quick thank-you, a public shout-out, or a personal note goes a long way. Encourage peer-to-peer recognition so appreciation comes from all directions, not just the top down.

- Check the Pulse Regularly Use short pulse surveys or informal check-ins to understand how people are feeling — about workload, culture, and well-being. Act on feedback quickly so employees see that speaking up makes a difference.

- Be Transparent About Challenges Don’t gloss over tough realities (economic shifts, AI disruption, restructuring). Acknowledge them honestly, explain the “why,” and share how you’re supporting employees through them. Even a simple “I know this is a difficult time, here’s what we’re doing to help” builds trust.

Happiness at work isn’t a perk or a slogan. It’s the outcome of deliberate choices leaders make every day — to invest, to listen, to support, and to trust. Employees don’t expect perfection, but they do expect authenticity and care. And when leaders get that right, happiness follows.

Check out our full podcast chat here : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jJkwto14YlA or through the image below….

…and check out more episodes of #FromXtoZ here – https://www.purpleacornnetwork.com/shows/from-x-to-z